New Yorkers can resurrect almost anything, as anyone who has wandered the High Line—a former railroad spur turned lofted greenway—might attest. Lewis Miller, however, can make resplendent beauty adding to things just as they are. Whether the floral and event designer is arranging a blitz of white anemones and sweet peas on a subway stop’s cast iron railing or placing hundreds of peonies in a galvanized metal trash bin, his street art installations—known as Flower Flashes—stop even the most harried city-dwellers in their tracks.

-

“Lewis is such a genius with gardening that I knew that would be part of the story,” says designer Matthew Kowles. “You enter through a garden that lends itself to the mystery of what’s inside.” The gate was custom-stained to match the Farrow & Ball Oval Room Blue trim on the house.

Carmel Brantley -

Miller stands under an archway of confederate jasmine. Olive jars from Devonshire Antiques in Palm Beach add a well-worn layer to the entry. Pendant light, Paula Roemer Antiques.

Carmel Brantley

The design team transformed the former living room into what is now the dining room, which features a mantel painted with a faux bois finish by artist Joseph Steiert and accented with Tabarka Maghreb tile. The floor was also custom painted, by Mary Meade Evans. A pair of antique caryatids, installed on the wall to the right, “are two of Lewis’s most treasured purchases,” says Steinle. Wallpaper, Studio Four NYC.

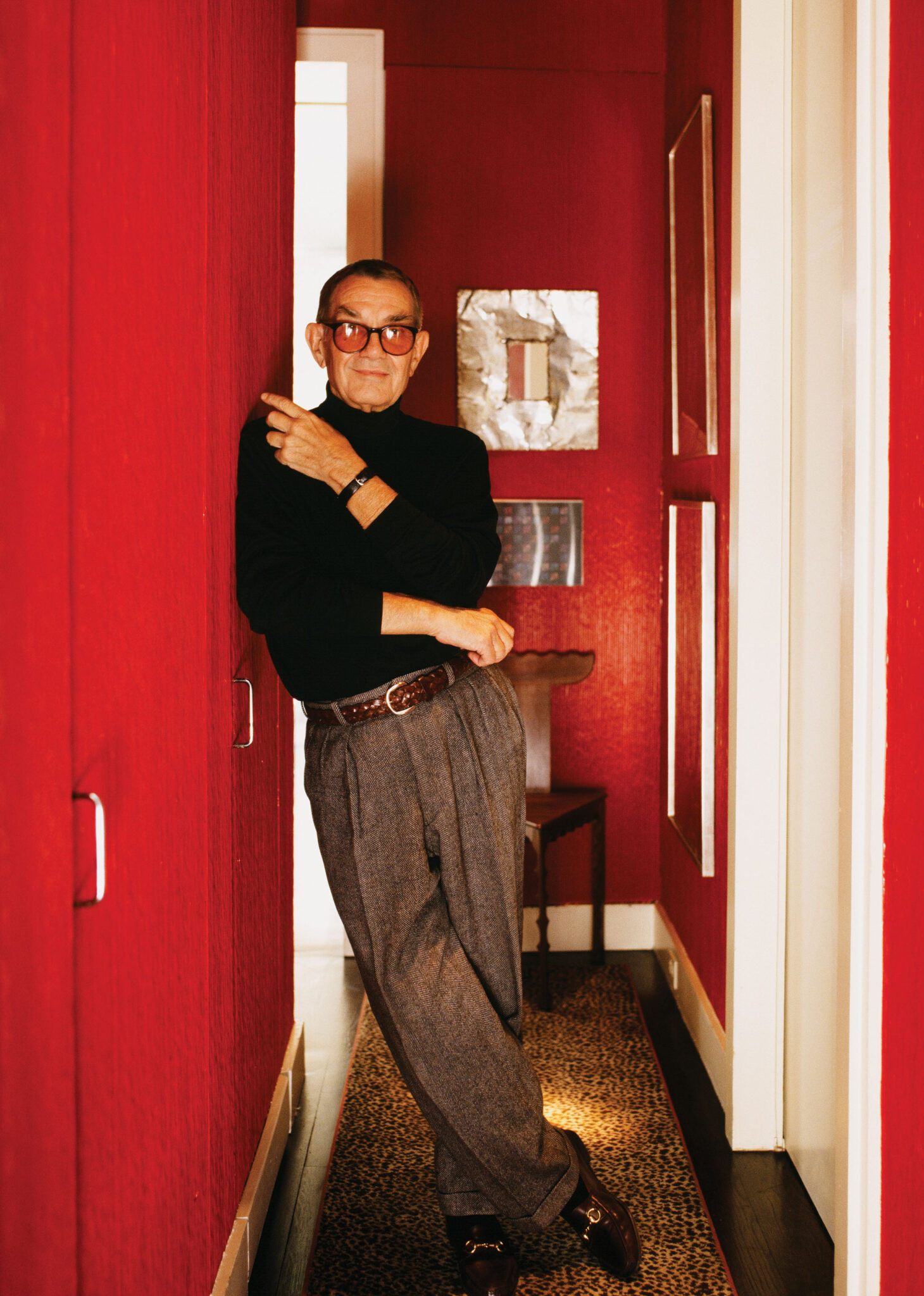

Carmel BrantleySo when Miller scooped up a 1926 Spanish Mission home in West Palm Beach, Florida, that was down on her luck—literally, as it sat sinking on its east side into the humid Florida earth—no one seemed to doubt that he could work magic to turn it into a showstopper. To get the job done properly, he enlisted a coterie of pros to revamp and restore the property, including Natasha Steinle of Romanov Interiors and architectural interior designer Alexandra Cargill Reynolds. “He’s a genius—he’s seriously a genius,” Steinle says. “And it comes out in his house.”

Miller’s good friend, designer Matthew Kowles, jumped in on the brainstorming meetings when he was honing in on the overall look and feeling of the home. “He gave me a few words—’Hemingway’s Florida,’ ‘the South before air conditioning,’” Kowles recalls. The resulting color palette is a bit muddy, “almost more like Hemingway in New Orleans or Cartagena and how that would be interpreted in a place in West Palm Beach. It was a fantasy.”

Emerald-green Zellige tile by Villa Lagoon sets the tone in the cookspace, which was inspired by Britain’s deVol kitchens. A parade of vintage pots, custom shelving painted in Benjamin Moore’s Essex Green, and brass details add to the storied effect. Sink, Rohl. Hardware, Newport Brass. Ceiling lights, Urban Electric.

Carmel Brantley-

“It’s so cozy,” Natasha Steinle says of the library. “I just envisioned curling up with a book and spending time in there.” Cane detailing adds texture to custom built-in bookshelves, painted in Pacific Rim by Benjamin Moore. Roman shades in Hydrangea Lace by Soane. Rug, Rush House.

Carmel Brantley -

Osborne & Little’s Cranes wallpaper paired perfectly with the powder room’s original tile and existing vintage pedestal sink, which is skirted in a Carolina Irving fabric. Sconces, Visual Comfort.

Case in point: Throughout the home, there are now small trompe-l’oeil surprises, hand-painted by Joseph Steiert Studio. “He texted me one day and he’s like, ‘I want to do some fun, whimsical sort of trompe l’oeil,’” says Steinle. “So the three of us [including Steiert] came up with a list of things that he wanted. Now, there’s a mouse on the staircase, a $50 bill by the bar on the floor, and a dead butterfly on the windowsill in the library.”

Unburied treasure abounds, much of which Miller has been secreting away for years in storage in New York before its moment in the sun. “There were what felt like thousands of boxes,” Steinle says, “but he knew exactly what he had. And the house, it sucked it all in. Everything had a place the minute we opened it.” One particularly exquisite find: a pair of caryatids that Miller found at Kofski West Palm beach. “He texted me a picture of them and said, ‘I just splurged and bought these!’” Steinle recalls. “I ran over to the house and my electrician electrified them on site, because I didn’t want to move them.”

Japon Garden grasscloth wallcovering from Hartmann & Forbes kicked off the design directive for the primary bedroom. “Our color palette and floor design were all inspired by the walls,” says Steinle, who used a pale aqua (Benjamin Moore’s Maid of the Mist) on millwork and enlisted Mary Meade Evans to paint the floor.

Carmel Brantley-

The 1926 home had few closets, so the team constructed a private dressing room with built-ins (painted in Farrow & Ball’s Dix Blue) to hold clothing as well as linens. The Fibreworks seagrass carpet and natural cane door inserts add to the relaxed feel. Window seat cushion in a Carolina Irving fabric. Hardware by Purdy Goods Shoppe through Etsy.

Carmel Brantley -

Because Miller has two guest houses on the property, what might have been a guest room in the main house has instead been transformed into the ultimate napping retreat, wrapped in Sunburst wallpaper by Robert Kime. The vintage bed, from Chairish, features hand-carved tobacco leaves on each post.

Carmel Brantley

Long after all the dust of the install had settled, pixie dust remains. “It’s pretty magical,” Steinle says. “I hadn’t been in there for a couple of months and just walked in there today to meet my upholsterer, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this place is so special.’” She notes that, like any grande dame, the house has its own signature scent—Pot Pourri by Santa Maria Novella, a pharmacy founded by Dominican friars in Florence, Italy circa 1221. “The house literally has character. It smells good, it looks amazing. It envelops you and your senses from the moment you walk in.” Hemingway would love it.

The upstairs loggia is a perfect spot for Miller’s morning coffee. “Almost all vintage pieces of furniture were found locally in shops on Dixie Highway and painted to coordinate if need be,” says Steinle, who found the stools at Devonshire Antiques and the sofa and chair at Show Pony Vintage. In keeping with Southern tradition, the ceiling is painted a pale shade of blue (Polar Ice by Benjamin Moore).

Carmel Brantley