Sometimes the design of a building can be the perfect expression of a particular time and place. Between 1961 and 1981, architect Horace Gifford created beach homes, primarily in the gay resort community of Fire Island Pines, that captured the exuberance and strength of a vibrant community coming into its own after the birth of the gay rights movement. Made of cedar and glass, open to the sky and sea, they invited celebrations and revelry. In fact, this writer met his spouse on the deck of an ocean-front Horace Gifford house during a Labor Day weekend afternoon party in the Pines many years ago.

Gifford was born in Vero Beach, Florida, a hamlet that his great-grandfather had founded. Tall, blond, and handsome, Gifford considered a career in modeling but instead pursued his passion for architecture. He attended the University of Florida where he fell under the spell of Paul Rudolph’s early modernist architecture, and later studied under Louis Kahn at the University of Pennsylvania. While working as an architect in New York, he discovered—and fell in love with—the community of Fire Island Pines on the car-free barrier island just 60 miles from the city. There, he began to build houses inspired by the strong, geometric shapes of Kahn’s work, but instead of concrete, stone and brick, Gifford used beachy wood and glass.

Gifford designed the Travis Wall house in 1972 as a series of telescoping cubes that frame the water view facing the Great South Bay.

-

Inside the house, sleek, stage-like tiers offer water views from every angle. All the furniture was built-in, including a dining pit with a glass table.

-

In a bedroom of the Travis Wall house, a provocative public view and voyeuristic vista were created with a plate glass wall and mirrored ceiling.

His vision for beach houses was a radical departure from the wooden cottages with small windows that populated Fire Island, and the traditional shingled houses of the Hamptons and New England. Mixing pure modernist forms like cubes, domes, cylinders, vaults and pyramids, he combined solid wood with walls of glass and eschewed traditional paint and plaster to create sleek, stylish designs stripped of any superfluous decoration.

Gifford practiced a sustainable approach before the term was popularized in architecture, using humble, naturally weathering, low-maintenance cedar inside and out. Thin anodized aluminum frames held glass windows that blurred the lines between interior and nature, creating rooms that seemed to “reach out and grab for light,” as the architect put it. Gifford encouraged clients to build smaller instead of bigger, and left most sites largely untouched except for a winding path leading to the house. Pulitzer Prize–winning composer Ned Rorem, who was a guest in a Gifford home, noted that residents “live simultaneously indoors and out.”

-

In 1975, Gifford created a tree house for attorney Lawrence Bonaguidi with a dramatic slanted glass wall that descends two floors to the foyer below.

-

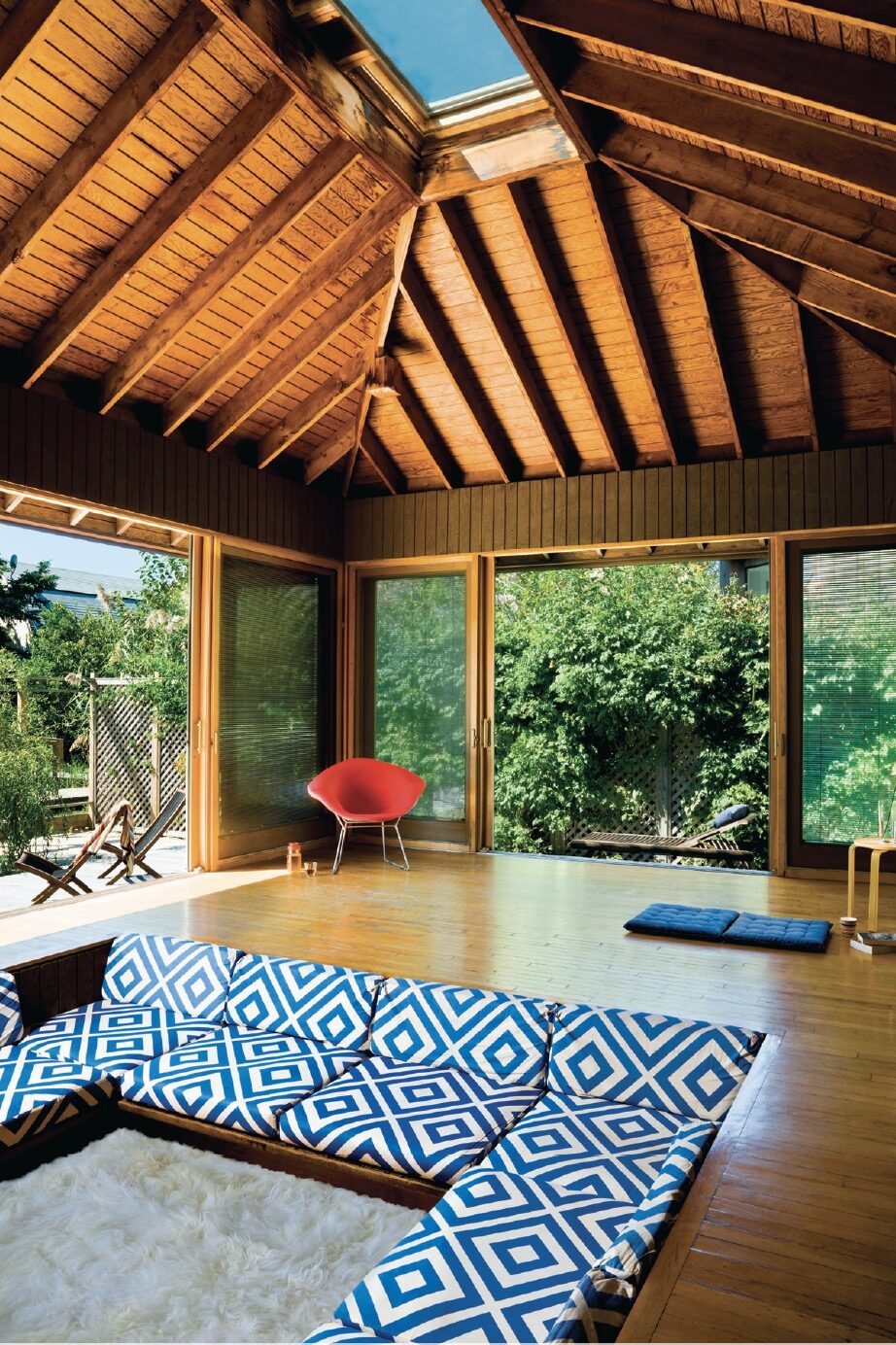

In 1976, Gifford designed a guest house with a high pyramid roof punctuated by a skylight for Sam and Joan Scali in the Fire Island community of Fair Harbor.

During his career, Gifford designed 63 houses on Fire Island (including 40 in the Pines) and 15 off the island. Tragically, he died of AIDS in 1992 at age 59, his name largely forgotten until his work was rediscovered by architect and historian Christopher Rawlins, who published Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction in 2013 (soon to be republished).

“I wondered why I hadn’t seen these houses in architecture school. It became a mystery to unravel,” says Rawlins. He uncovered colorful stories and anecdotes about Gifford, who was said to stroll along the beach on his way to meetings while wearing a Speedo and carrying an attaché case. Another contemporary recalled that the designer once remarked to a client that, in his spacious new house, he’d “have 20 closets to come out of.” “What struck me is that his architecture really cannot be separated from the culture that he created the houses for,” says Rawlins. “They weren’t just vacation homes; they were stage sets for this emerging, more liberated generation of gay men.”

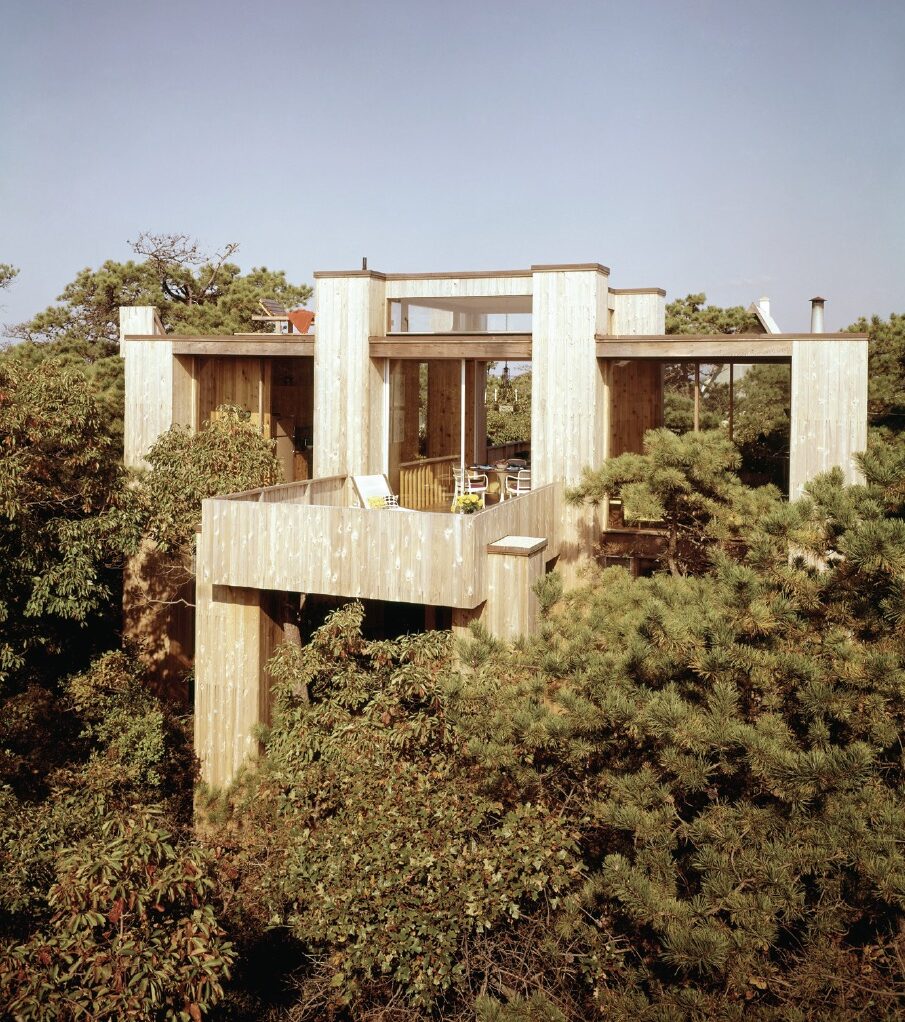

At 603 Tuna Walk, Gifford built a house for textile designer Murray Fishman in 1965 that rises out of the scrub bushes and pine trees on 12 muscular columns.

Rawlins is currently updating several Gifford houses, including one that was owned by Calvin Klein and then David Geffen. “If you understand the underlying principles behind the house, you can fit in an en-suite bathroom or add a pool with finesse,” he observes. The architect also conducts guided house tours in the Pines and maintains the Pines Modern website, a well-researched, free, non-profit educational archive of Fire Island architecture.

Today, Gifford’s work continues to inspire designers, including Miles Redd, who owns a Gifford-inspired Pines Modernist house. “In the city, I love colorful, dense interiors—marble and lacquer and horsehair and soigné—but at the beach, I want wood and beige and simplicity and sex appeal, and nobody did that better than Horace Gifford,” says Redd. “He worked with very simple components and not a lot of square footage, but he thought about space as sculpture and had an eye for cheap materials that he could make stylish.”

On the second floor of the Fishman house, the single large open, space for living and dining areas is signature Gifford.

The luxury and sensuality reflected the locale. “The Pines is still a place where gay men go and another shackle is taken away,” says Redd. “They feel just a little bit freer, and it comes out in the architecture.”

After my spouse-to-be and I met on the deck of the Gifford house that he was renting with friends, the two of us returned for an end-of-summer weekend. It was many years ago, but I remember well the deep conversation pit and the ground floor bedroom; with its big glass wall looking out on the ocean, it was like sleeping on the beach. We had a great weekend in the house (though it was destroyed shortly thereafter by Hurricane Gloria) and still celebrate our anniversary on the day that we met there. Gifford may have passed away in 1992, but his work continues to cast its allure across Fire Island Pines.