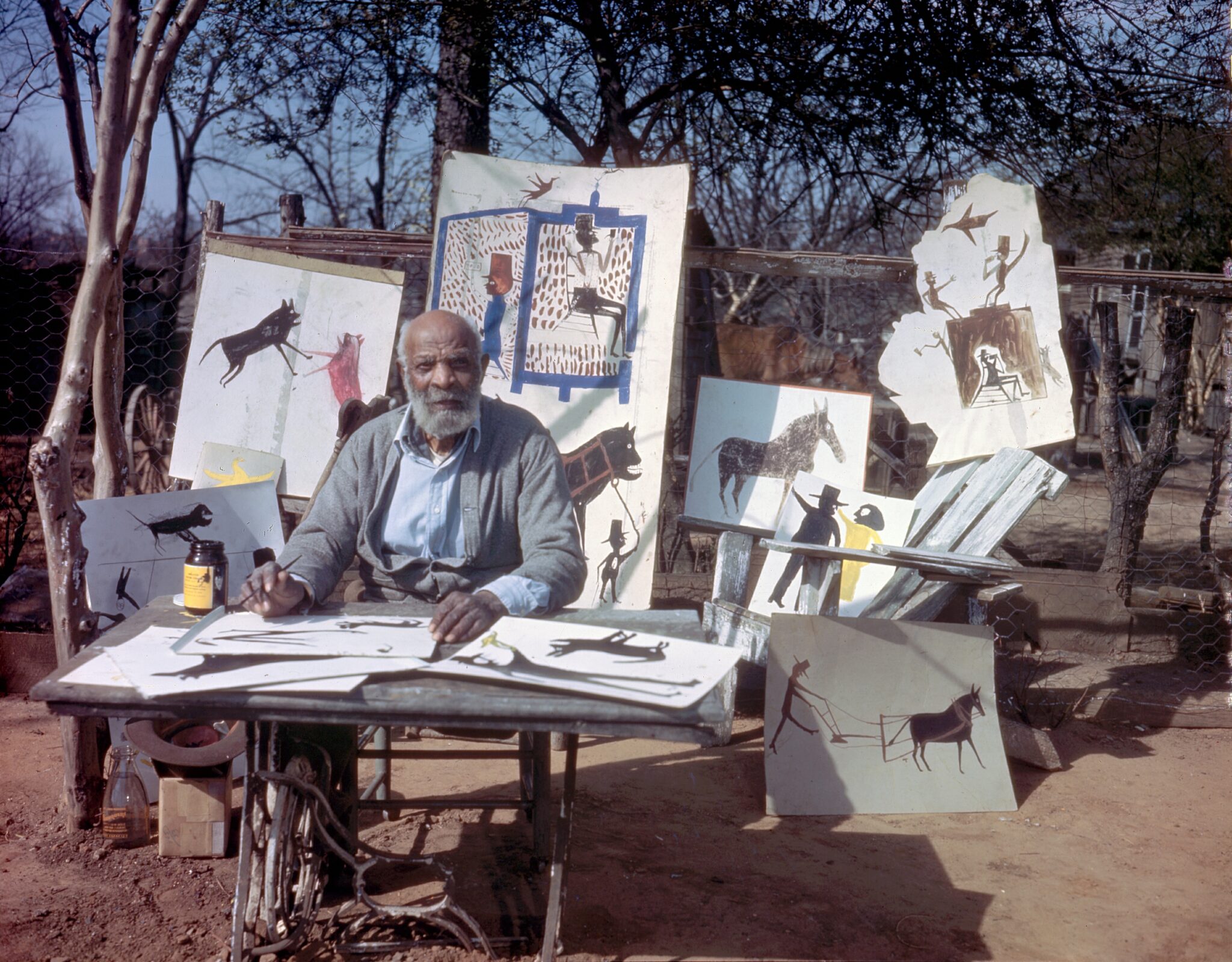

Artists hold a unique position as witnesses and real-time recorders of the cultural and geographical periods in which they practice, a trusim no better illustrated than in the art of Bill Traylor. Born into slavery in Alabama around 1853, Traylor was emancipated in 1865, but remained a sharecropper on the same plantation for another 45 years. It wasn’t until he was in his eighties, living on the streets of segregated Montgomery, that he began drawing and painting.

“He came to his art without training, without precedent, and created some of the most captivating imagery of 20th-century American art,” says Jonathan Laib, a senior director at David Zwirner in New York, where Traylor’s most recent solo show is on view until April 13th. Self-taught and unable to write, Traylor communicated through his art—much of it created while working on a street corner—the dramatic social and political changes he witnessed during the first half of the 20th century, giving us a better understanding of the personal impact slavery had on his life and the lives of other Black men, women, and children in the South.

-

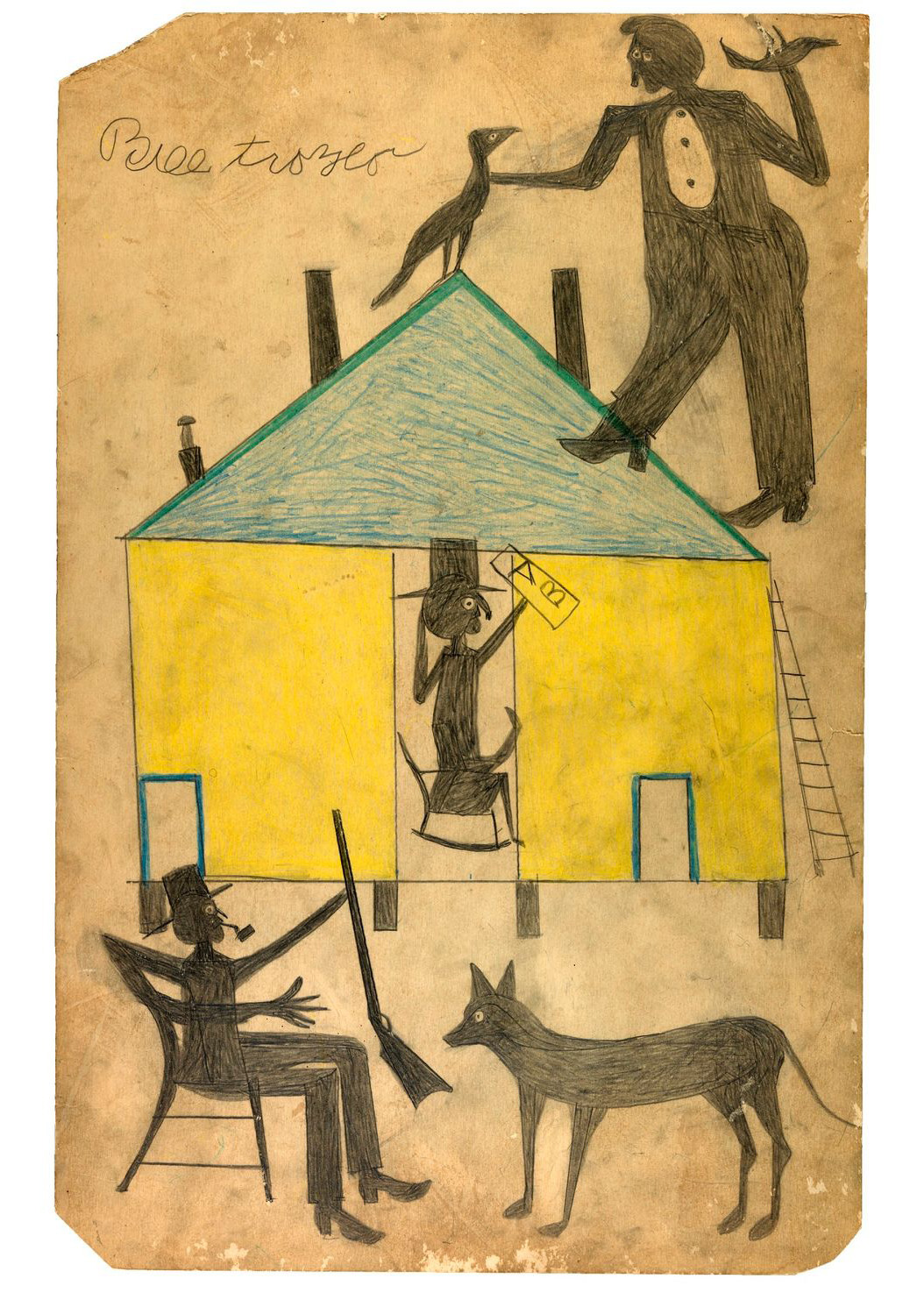

Bill Traylor, Untitled (Yellow and Blue House with Figures and Dog), 1939, colored pencil on paperboard.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2016.14.5, © 1994, Bill Traylor Family Trust -

Bill Traylor, Untitled (Radio), ca. 1940-1942, opaque watercolor and pencil on printed advertising paperboard.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2016.14.4, © 1994, Bill Traylor Family Trust.

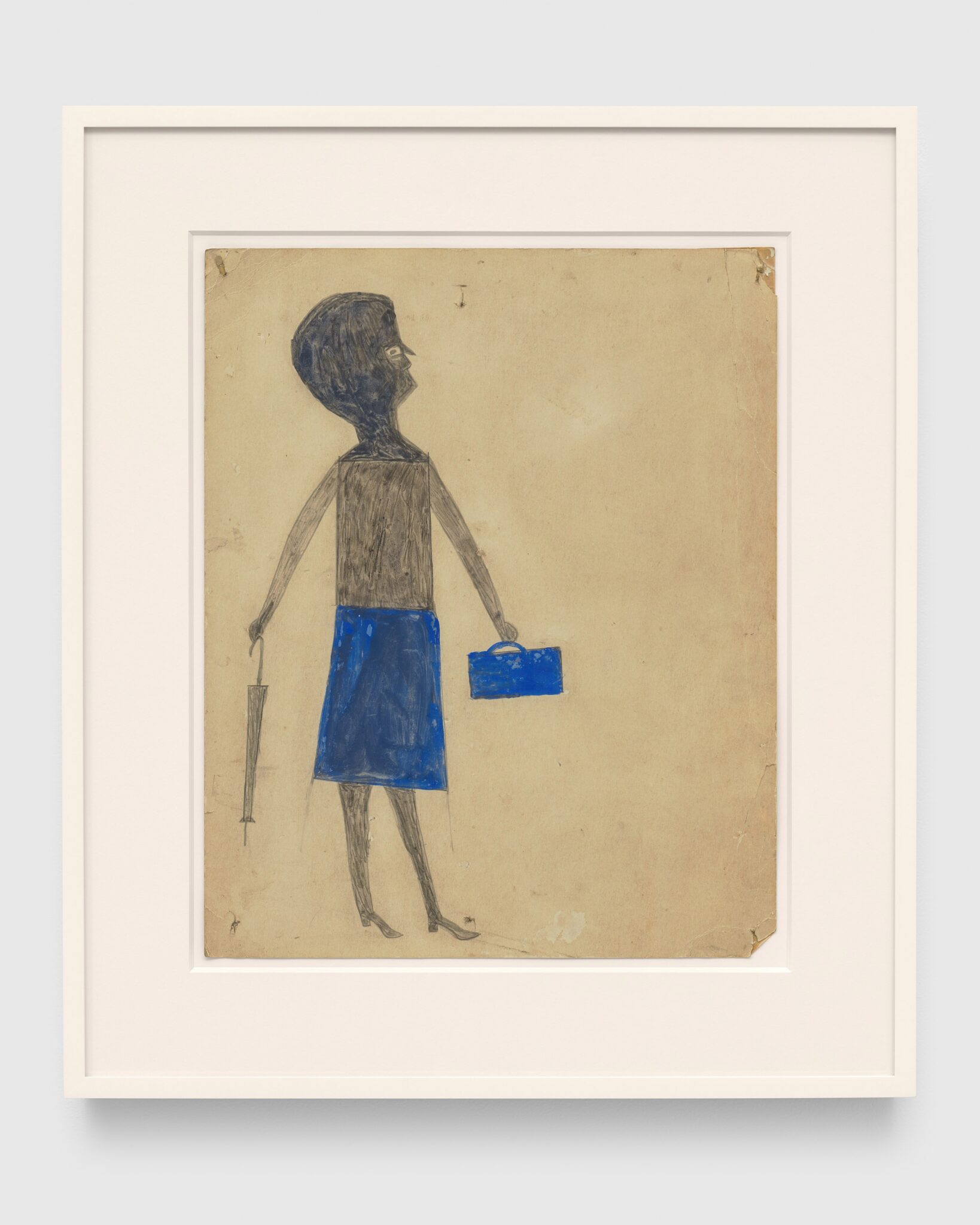

“[Montgomery] was culturally entrenched in its old ways even as it moved inevitably towards a future that looked very different,” says Leslie Umberger, the Smithsonian American Art Museum curator who mounted the first major institutional retrospective of Traylor’s work in 2018. “Traylor’s images tell more than one story, but his depictions of African Americans rising as a proud and distinctive culture are striking. He portrayed men and women doing farm labor—plowing the field or carrying a basket—but it is his urban scenes that directly describe a free life. The people he painted have their chins uptilted, looking at what’s ahead and doing so with pride.”

An installation view of “Bill Traylor: Works from The William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation” at David Zwirner, New York, February 22–April 13, 2024.

Courtesy of David Zwirner. All Bill Traylor artwork is used with permission from Bill Traylor Family, Inc.Traylor’s other subjects range from innocent—and sometimes even humorous—animals to more challenging symbols of oppression and enslavement, like chained dogs and men wielding rifles and axes. Such depictions were an act of courage: As a Black man in the Jim Crow South, Traylor risked his safety and that of the people around him by truthfully presenting the atrocities he witnessed. “Traylor had the ability to fly under the radar of white Montgomery by using visual codes—colors and allegorical structures for telling stories in a way that led Black and white viewers to different understandings of what the images might be saying,” explains Umberger.

Living in poverty at the end of his life—his work didn’t receive widespread recognition until the 1980s, long after his death in 1949—Traylor used scraps of paper and found materials as his canvases, exaggerating the impact of his subjects by creating a site-specific element in two-dimensional work. “His drawings provide a lesson in frugality, celebrating cast-off materials which bring with them their own histories and imperfections,” says Laib. “Their use erases the boundaries between art and life that hinder so many artists today and throughout history.”

-

Bill Traylor, Blue Dog, 1939-1942.

Courtesy of David Zwirner. All Bill Traylor artwork is used with permission from Bill Traylor Family, Inc. -

Bill Traylor, Woman with Blue Purse and Umbrella, 1939-1942.

Courtesy of David Zwirner. All Bill Traylor artwork is used with permission from Bill Traylor Family, Inc.

Taking cues from the rich cultural traditions of Blues music in the South, Traylor’s art is melodic, rhythmic, and deeply emblematic. His work stirs emotions in the same way that a song can move a listener when the right chords are struck. Today, his evocative pieces stand as a testament to the endurance of the human spirit and the role that visual histories play in the continuation of cultural traditions, serving as inspiration—and education—for generations to come.

The second solo show of Traylor’s work presented by David Zwirner comes from the illustrious collection of the late William Louis-Dreyfus, an avid collector and supporter of self-taught artists. Proceeds from the exhibition will benefit the Harlem Children’s Zone in an effort to end intergenerational poverty.