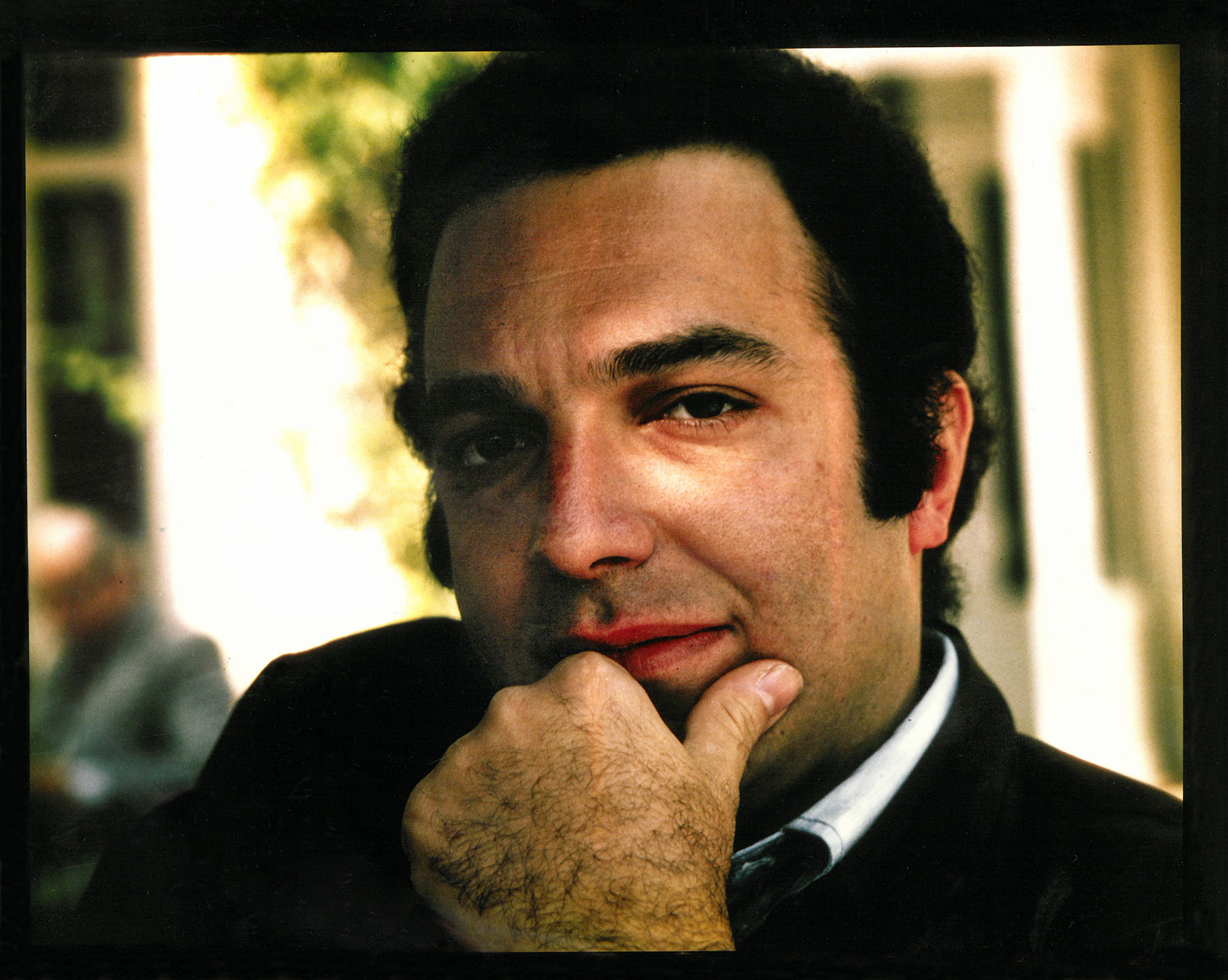

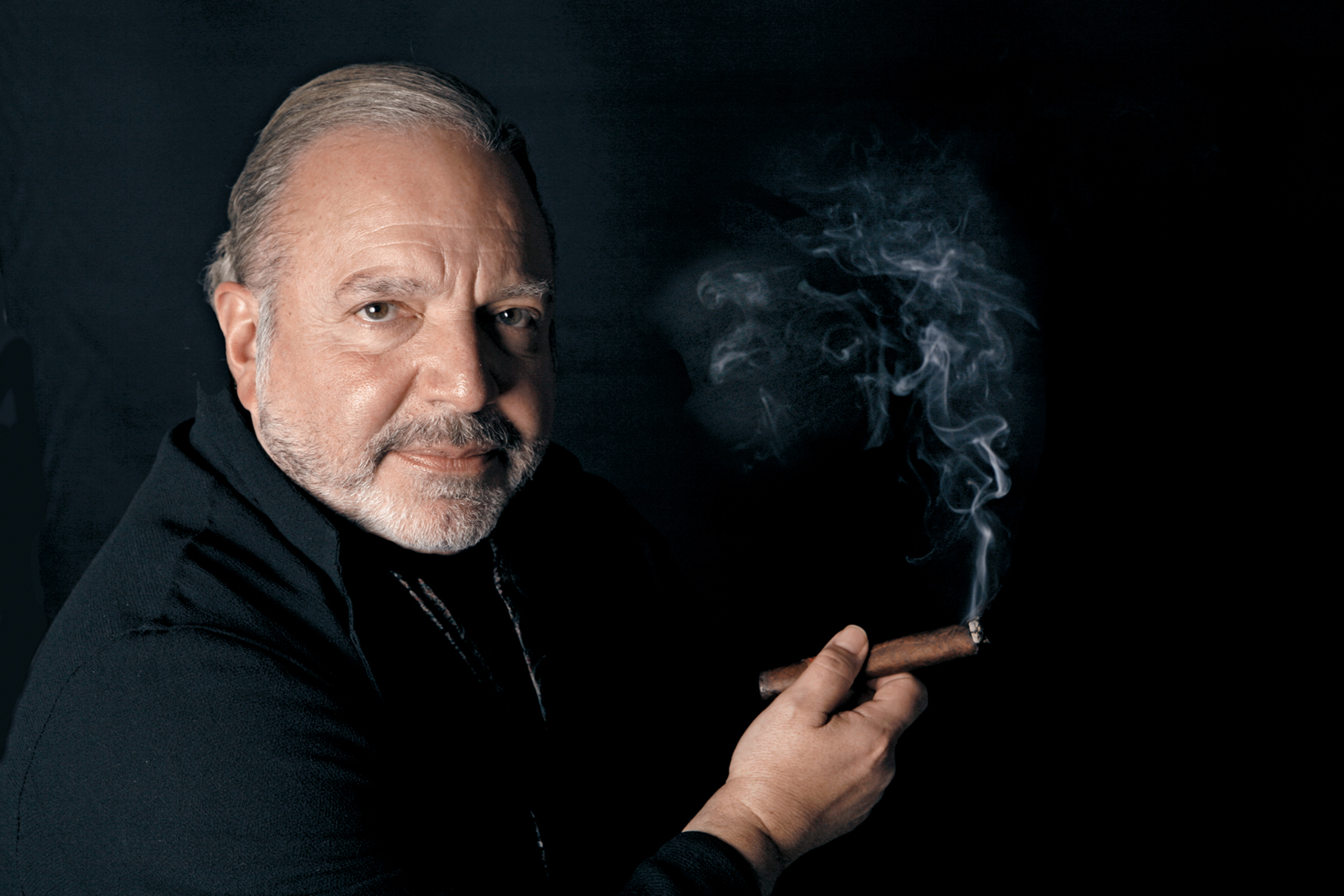

In 1971, John Saladino, his wife, Virginia, and their newborn son moved to Beekman Place, a two-block-long, tree-lined hideaway near the United Nations, considered one of the most exclusive corners of Manhattan. There, Saladino crafted a space that displayed his skill at creating drama and mixing textures, styles and pieces from disparate cultures and eras—a pioneering practice that became a personal trademark and changed the evolution of design. Below, he takes us back to that first apartment.

Deliver us to Beekman Place

The apartment was a sort of Fred Astaire—Ginger Rogers Art Deco two-bedroom with two baths, a little dinette and a kitchen, in a 1930s brick building on Beekman Place. The street was made very famous by the musical Auntie Mame, where Mame would sing, “Deliver us to Beekman Place!” It’s like a secret street, an oasis, but it’s still in Manhattan. We had a silver view of the East River and we looked down on the United Nations Plaza.

Modern Times

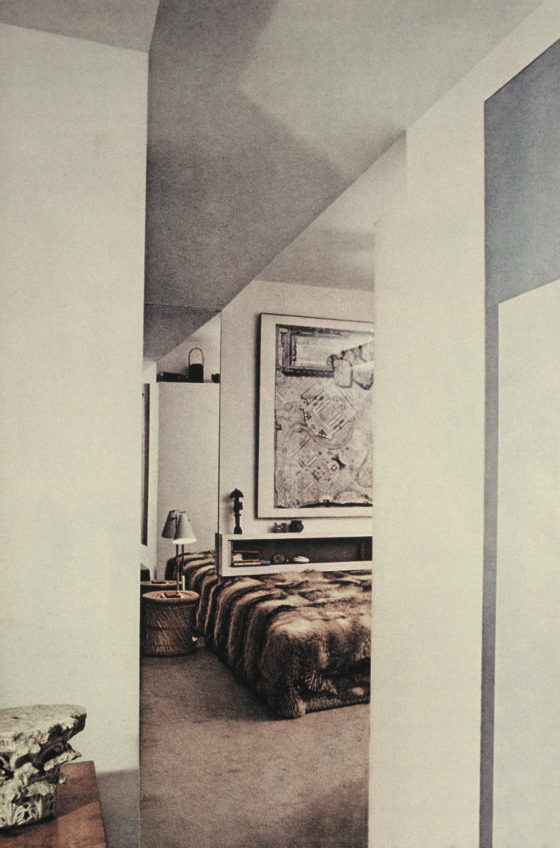

I wanted to double the living room’s size and create a flowing one-room space that was very International in style, and I wanted to have central air conditioning, so I gutted the apartment and made it into a one bedroom. I made the shell of it very modern: I got rid of all the baseboards and dropped the ceiling about 11 inches, which gave me space for air conditioning ducts and emphasized the flowing nature of the space.

-

A space-age, underlit platform topped in café au lait–colored carpeting frames an 18th-century Ghiordes prayer rug. The painting, featuring three different types of aluminum paint, is by Saladino.

COURTESY OF GRAHAM SALADINO -

At 19, Saladino spent $300—which a Los Angeles art dealer allowed him to pay in $50 installments— for a rare Giovanni Battista Piranesi etching that later hung in this bedroom. Only three or four were ever produced; the others were purchased by Louis Kahn and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

COURTESY OF GRAHAM SALADINO

Breaking the Rules

At that time, in the beginning of my career, most of my work was very modern. And then it changed as tastes changed. But I was probably the first person to mix antiques with International-style architecture. That was a no-no. If you had a white International room, you had all Bauhaus furniture. But I didn’t. I mixed a lot of antiques from different cultures together. We had a Bauhaus-style dining table, and hanging above it, a William and Mary triangular mirror from about 1690 veneered in clamshell burl walnut. The wall behind it was horizontally striped in a high-gloss-and-matte finish in taupe. I got the idea from a cathedral in Italy.

How to Build a Classic

I’ve always chosen things with simple geometric forms. I like cubes and drums and circles and triangles, and everything in that apartment was based on those primary shapes. The sofa and the leather mattresses were rectangles. The round wicker chair from Denmark was a sphere. The ottoman was a circle. I was putting together things from different times and around the world, but everything had a very simple geometry, and I think that is the reason the room still doesn’t feel dated. That was my intention: that everything I designed would last and be classic.

Signs of the Times

People were very, very inventive at this time. The 1950s had been very kind of West Point regimental, and then all of a sudden, there was this huge freedom. I installed flush lights under the step-down platform, which was part of the gestalt of that period: Everything was made to look like it was floating, to exaggerate the space, make it look bigger. You could see the reflection of the light against the polished oak floor next to the daybed. Above is a mirrored ceiling—the panels of the glass were held in place by half columns, which completed themselves as full circles in the mirror. And then there was the fur bedspread. My wife hated it because it weighed so much. I would never do a fur bedspread now because it’s a little too disco, but it was very chic for its time. I mean, that’s Studio 54.

The Golden Age

Virginia was a very accomplished cook. She was also an interior designer who had worked for the Stanford White firm, and together we were a pretty impressive team, if I may say so. She taught me that wherever you go, you buy a piece of silver, so at the end of your life, instead of owning a lot of crummy antiques or books that you don’t read anymore, you can open up the silver chest and remember where you bought that plate or that creamer or that serving fork. That became part of how we set the table and the stories we told. We didn’t have big parties in that apartment—we did at our place in Connecticut—but we could fit six at that table. Virginia used to do a tomato aspic and chicken Marbella, and we would get caviar from Petrossian and have that with cocktails and Brut de Pêche—peach champagne was big then. It was nice. We had a good life.

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of FREDERIC. Click here to subscribe!