For decades, Barbara D’Arcy’s extraordinary and exuberant “model rooms” at Bloomingdale’s were the toast of the town. The late decorator upended conventional style and established a bracingly new visual lexicon that endures to this day.

D’Arcy was central to this metamorphosis. “If Barbara D’Arcy isn’t a household name, she certainly should be,” wrote the legendary retailer Marvin Traub in his 1993 memoir. But as he knew, D’Arcy’s force was like a weather front: Indomitable, pervasive, yet invisible. In time, everyone knew what they liked, they just didn’t know who’d made them like it.D’Arcy was born in New York City in 1928 to an art-teacher mother and a father who managed a moving and storage company that gave him a keen eye for furniture. They took their daughter for long walks through the city, looking at antiques shops and instilling in her a unique sense of style—“not school-taught, but city-bred,” as Traub put it.

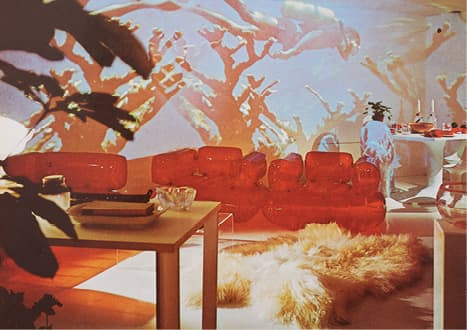

In 1952, after graduating from the College of New Rochelle with a degree in art, D’Arcy started work as a junior decorator in the fabrics department at Bloomingdale’s, a few blocks from where she’d grown up. In short order, she invented a whole new method of retail display: Rather than lining up furniture in a row, as had long been the norm, she designed entire vignettes that included everything from sofa to ottoman to rug, embarking on flights of fancy never before seen in a store and pulling in a dazzling array of references.

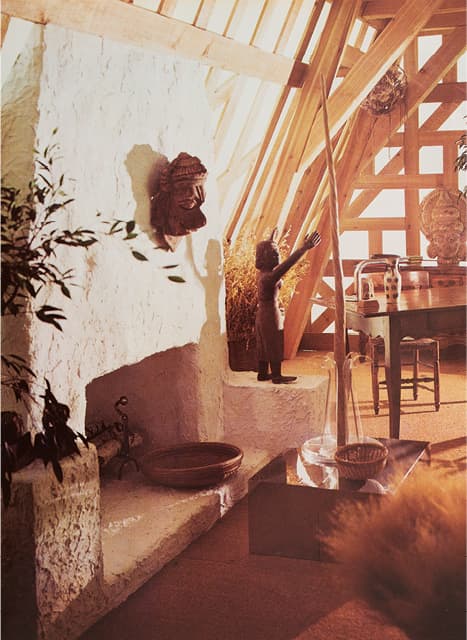

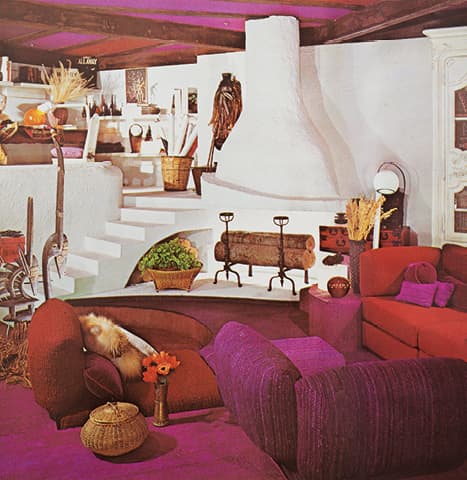

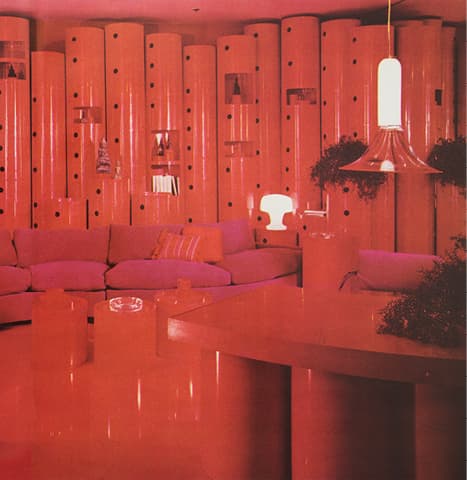

D’Arcy’s rooms were the original pop-up stores, open to anyone and everyone who wandered by, and people flocked to them. What she sold transcended furniture—those visitors who didn’t part with a penny still walked away with new ideas about color, pattern and taste. Take, for instance, her famous 1972 Cave Room. Inspired by the French architect Jacques Couëlle, D’Arcy dreamed up an open-plan, white-stucco fantasia, using chicken wire and spray-on polyurethane to sculpt a living-dining-bedroom space with a series of steps, a fireplace and a conversation pit filled with purple cushions (one of her favorite colors).

“And,” Kron continues, “she accessorized herself like she accessorized her rooms—she was always dressed impeccably, colorfully, with the most wonderful jewelry. When we were all in pantsuits, she was wearing long Mexican skirts down to her ankles. And she didn’t give a damn that she didn’t have a model’s figure.”

D’Arcy also made a lasting imprint on her employees, many of whom went on to flourish in and shape the industry themselves. Mitchell Gold, cofounder and chairman of the furniture company Mitchell Gold + Bob Williams, began his career at Bloomingdale’s in 1974 selling pillows. “It was dazzling to see her brilliance,” he says. “Her model rooms were set design, she brought theater into the store. Knowing her and watching her work made me reach for the stars, reach beyond what I was capable of doing, and look for better things to do.”

The influential fashion editor and creative director Candy Pratts Price, who started at Bloomingdale’s in the mid-1970s doing window display, has similarly fond memories. “She was an incredibly creative woman, and always supportive of my spunk,” she says. “She had a fantastic office with a beautiful ficus tree—unusual at the time—and she was always dressed in Yves Saint Laurent, camel-hair capes, fabulous rings, hairdos from the salon.”

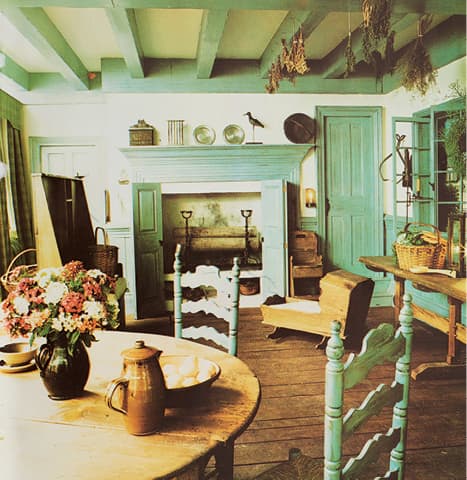

“I dislike: Imitation brick, phony wood paneling, pressed wood graining, plastic flowers and most lamps. I particularly hate period furniture that’s not true to style—whether the furniture is original or a copy. I think one should stick to the authentic in furniture as well as architecture.”

Her list of “likes” was much longer. It included rough plaster, plank floors, highly polished chrome, four-poster beds, books of every kind (“All rooms need books”), fabric-covered walls, heavy moldings, 17th-century furniture, area rugs, animal skins, “and, finally, I like lavender and orange. Together.”

Today, D’Arcy’s style is as relevant as ever. Her urge toward authenticity, wide-ranging appetite for beauty, relentless inventiveness, and fearless high-low mixing are timeless qualities that improve any room—or life, for that matter. Thanks to her, we denizens of the 21st-century take for granted that, far from being static, taste is an ever-evolving point of view. As she once wrote, “The final goal of designing and decorating a room is to create atmosphere. And atmosphere is style. That’s what it’s all about.”