Bertel Thorvaldsen was just a boy when he began his studies at the Royal Danish Academy of Art, a young man when he left to study in Rome, and nearly 70 when he finally returned to his native Denmark, in 1838. But during the 42 years intervening, his neoclassical sculptures earned him international fame. Copenhagen gave him a hero’s welcome—as well as his own museum, the country’s first. Erected in the heart of the city, alongside the Christiansborg Palace, the Thorvaldsen Museum opened its doors in 1848, and nearly 175 years later, remains virtually unchanged: Nearly 100 rooms, some used for archives and staff, the rest showcasing more than 400 of Thorvaldsen’s works and his vast collection of antiquities, all surrounding an inner courtyard in which the artist himself is buried.

This single-artist museum isn’t merely an homage to one man’s creative output. It also immortalizes the genius of its architect, Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll, a man who traveled as widely he as he read, achieving with this commission what’s known as a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art, in which the interplay of art and architecture creates a cohesive whole. Having attended the then-recent excavations of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Nero’s Domus Aurea in Rome, and visited then-brand-new museums in Berlin, Munich, and Paris, Bindesbøll drew on these and a variety of other influences, including ancient Egypt and the Bible, to decorate the ceilings and floors. Rather than simply replicate these disparate sources, however, he unleashed his prodigious imagination to create what present-day museum director Annette Johansen calls, “a melting pot of different countries, motifs, and inspirations.” The resulting mix of graphic mosaics, rich, pigmented colors, and delicately detailed frescoes and reliefs continues to inspires with its timelessness.

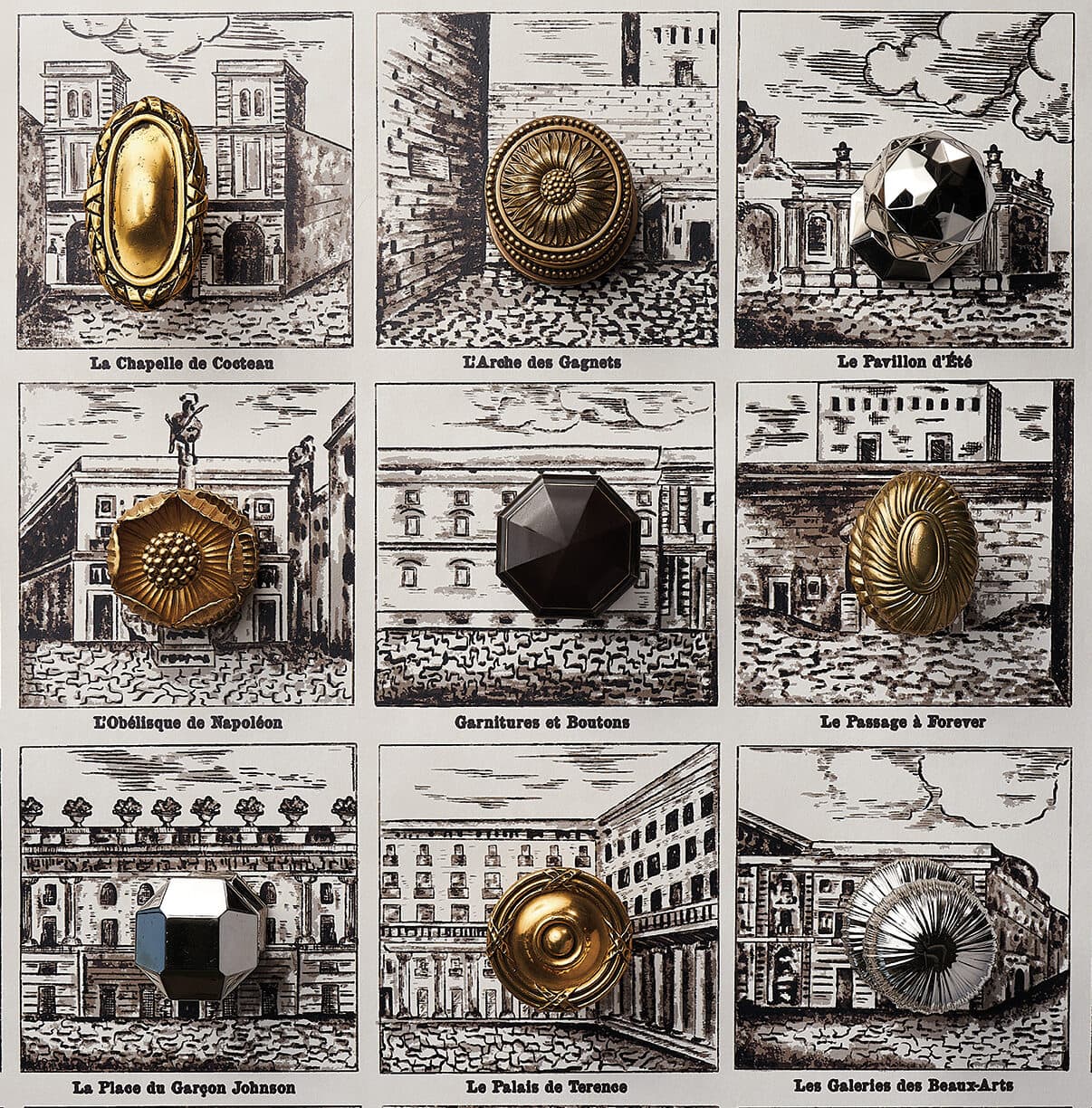

-

For the Northern Corridor, architect Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll sought to capture the sensation of walking through an ancient Italian loggia while looking up at a sky full of stars.

SARAH COGHILL, THORVALDSENS MUSEUM -

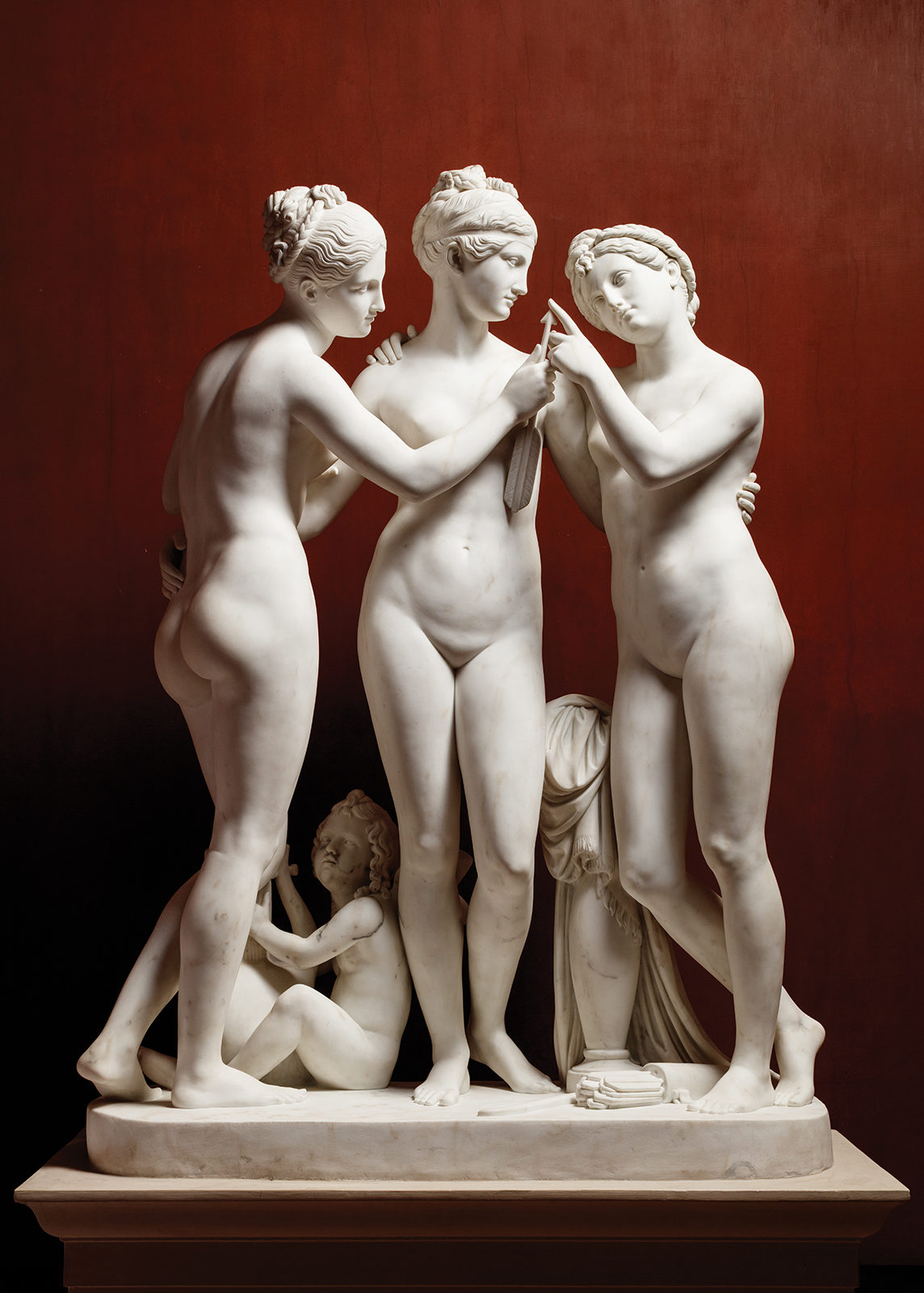

The Three Graces sculpture, also by Thorvaldsen.

JAKOB FAURVIG, THORVALDSENS MUSEUM

The proportions of the Grand Hall were modeled on Thorvaldsen’s own atelier near Piazza Barberini in Rome. The rest was dreamed up by Bindesbøll: Stucco rosettes line the barreled ceiling, the floor is tiled in a Nordic interpretation of a Pompeii-esque mosaic, and the walls are painted caput mortuum, a rich, dark brown hue originally made from mummified bodies that skews from purple to maroon depending on the time of day.

THORVALDSENS MUSEUMTHIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE FALL 2022 ISSUE OF FREDERIC. CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE!