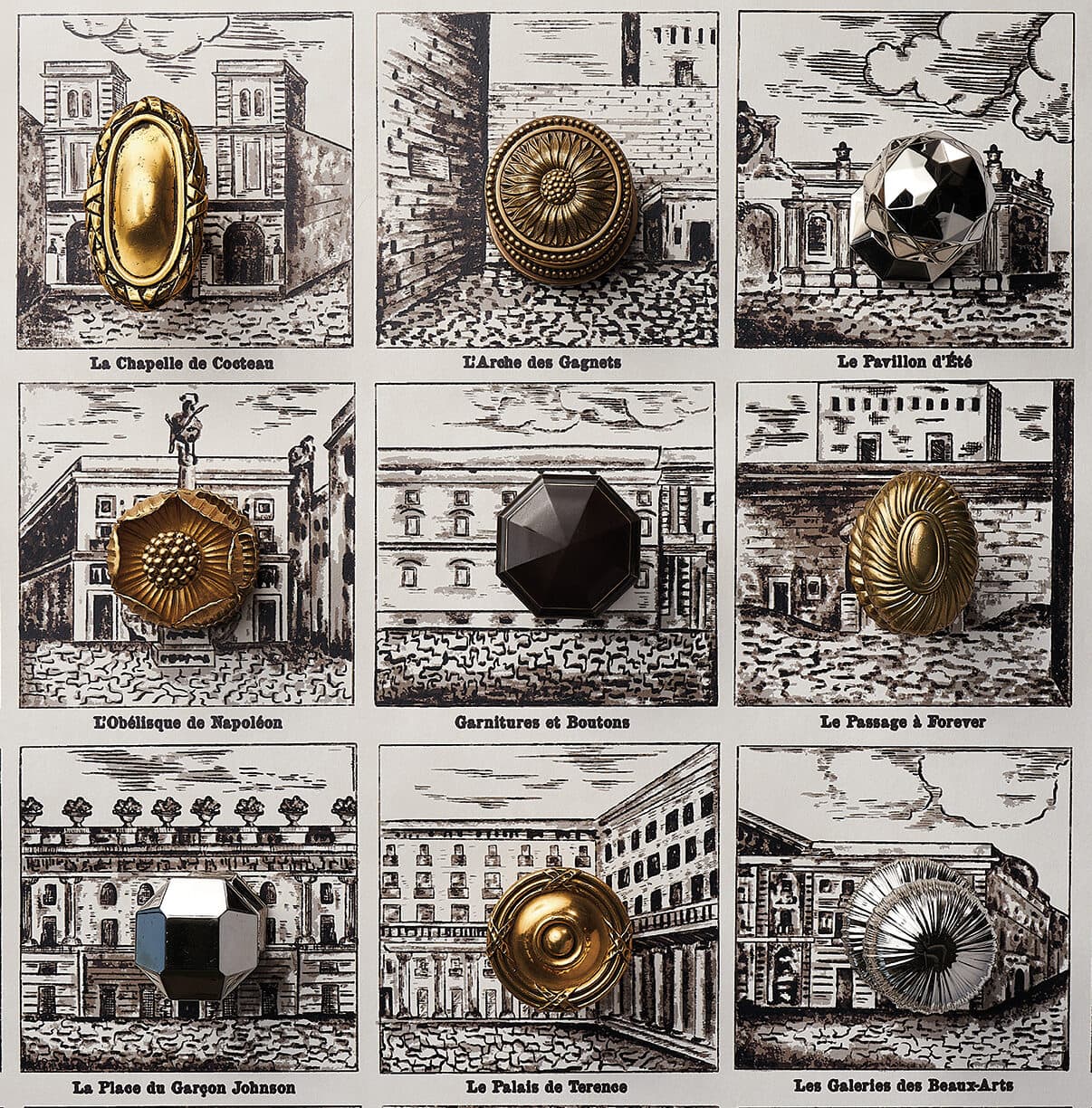

A farm-stand fruit basket rendered in gleaming vermeil. A paper clip vastly magnified and crafted in yellow gold, though otherwise indistinguishable from its office-supply inspiration. Ditto a ball of twine, a clothespin, and even an egg—a pantry basic that would be inventively and repeatedly refashioned in gem-spangled form by Fabergé, the jeweler to Russia’s tsars. Call them objets d’amuse: everyday items that have been made truly exceptional by their unexpected transmutation into precious materials.

Sketches of Elsa Schiaparelli’s Shoe Hat (1937–1938)

ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS) NEW YORK“Translating the usual into the unusual dates back to antiquity, when the leather pouches for holy water that were carried by Christian pilgrims in the Middle East began to be imitated in silver and porcelain by Chinese artisans, but I think we can actually blame the enduring fascination on Surrealism,” says R. Louis Bofferding, a Manhattan decorative-arts dealer and design historian with an admiration for the unorthodox. “An artistic movement that was avant-garde in the 1920s, thanks to René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, and their pioneering like, had become chichi by the 1930s. Fashion designers, especially Elsa Schiaparelli, found it amusing to fasten haute-couture suits with buttons in the shape of crickets or to offer clients a wool hat in the shape of an upended high-heeled shoe.” It could be argued, he adds, that a similar impulse led Jasper Johns to make Ballantine beer cans in bronze in the 1950s, Andy Warhol to hand-paint replicas of Brillo boxes in the 1960s, and Venini’s artisans to mouth-blow Murano glass into a light fixture in the shape of an incandescent light bulb in the 1970s.

-

Murano glass lightbulb (c. 1970s) by Paolo Venini

COURTESY OF PAMONO & JONATHAN ZELORI -

Silver fruit basket (c. 1965–1969) by Van Day Truex for Tiffany & Co.

COURTESY OF TIFFANY & CO -

Aphrodisiac Telephone (1938) by Salvador Dali

COURTESY OF MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART

-

Sterling Silver Ball of Yarn (2017) by Reed Krakoff for Tiffany & Co.

COURTESY OF TIFFANY & CO -

Brillo Box (1964) by Andy Warhol

© ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS -

Hen Egg (1885) by Carl Fabergé

Brevity is the soul of wit, as Shakespeare once said, so it stands to reason that when it comes to objects that bring a smile to one’s lips, those that can be held in one hand are the most prized—diversions that can be cradled close and gazed upon with a sense of wonder, a bit like the treasures in a princely Wunderkammer. Consider, for instance, Tiffany & Co.’s transformation of the humble punnet, the mignon wood-slat basket designed to hold berries at a produce stand, from flimsy wood to modish silver and vermeil. Its creator, Van Day Truex, Tiffany’s design director from 1956–1979, had come of age in Paris in the 1930s and brought the Surrealist chic that he saw abroad to the tabletops of America’s Social Register set, reimagining everything from fruit-shaped silver pill boxes to the Dyonisos decanter, a leaded-glass simulacrum of a mass-produced wine bottle that he conjured for Baccarat in the 1970s. An example of that crystalline vessel holds a place of honor in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—which goes to prove that tomfoolery can have a serious impact.

THIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE FALL 2022 ISSUE OF FREDERIC. CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE!