With the release of Lotusland, a new tome from Rizzoli about the 37-acre garden built by Polish-born opera singer Madame Ganna Walska in Montecito, California, author and literary historian Kate Bolick takes a look back at the idiosyncratic woman who devoted herself to its creation.

Madame Ganna Walska could have been a character in an Edith Wharton novel. Take the primary characteristics of the author’s most famous heroines—Lily Bart’s irresistible beauty, Undine Spragg’s blind ambition, Countess Olenska’s mysterious elegance—douse them with gasoline, and you get the bonfire of their vanities: a Polish child of the middle class who grew up to burn through six husbands (four incredibly wealthy, one a harebrained inventor, the last a yogi/con artist), struggle through a 20-year opera career, and eventually find her true self 6,000 miles away from home, on the coast of California, growing plants.

Come to think of it, Wharton had too much sense to try and concoct such an outrageous character. Nobody would have believed her.

Ganna Walska wasn’t her real name. Born in 1887 in Belarus, she was christened Anna Puacz and known as Hanna; at age nine, when her mother died, she was sent to St. Petersburg to be raised by family, and eventually made connections to the royal court. It was there she decided to become an opera singer, and wed a Russian—only to discover, on the eve of a charity performance, that a married woman’s name couldn’t appear in print. “Like all Poles, I loved to dance, especially to waltz,” she writes in her memoir, Always Room at the Top. “So suddenly I said, ‘Waltz, Valse, Walska …!’” As for Ganna, it’s the Russian version of Hanna. An opera diva was born. The marriage quickly went south.

In the winter of 1940, Walska paused to re-read the manuscript of her almost-completed memoir and had to restrain herself from tearing it to pieces. At 53, she was living alone in a grand apartment on Park Avenue, reflecting on a tumultuous romantic history, a short-lived perfume business (“Divorcons” was a bittersweet oriental scent), and an opera career that inspired reviews such as “incredibly bad singing,” as Time wrote after her 1929 performance at Carnegie Hall. But it was the very recent past that was causing her the most angst.

Over the decades, in pursuit of inner peace, Walska had tried psychics, Ouija, yoga, astrology, metaphysics, Christian Science, hypnotism, telepathy, theosophy, spirituality, and Rosicrucian philosophy, along with the teachings of an English religious fanatic. There was also something to do with fingers and magnets. Then, in 1938, an Englishman who claimed to have invented a death ray—I am not kidding—became the next in a long line of men to fall in love at first sight with her curvy, raven-haired self, and propose marriage. (This I believe to be true, based on how frequently it seems to have occurred.)

She was unimpressed. Haggard, bilious, litigious, and paranoid, the inventor was hardly a catch. At this point, Walska had already been widowed and divorced four times. It was all getting to be exhausting. But this latest suitor was in the English Who’s Who—and, at a certain angle, she could see a resemblance to Goethe. So when the British government “and certain English patriots,” worried that Walska’s indifference would kill the inventor before his method for detecting submarines could reach the War Ministry, begged her (allegedly) to “give him some hope,” she complied.

Soon enough, the powerful allure of being attached to a prominent man, combined with her delusions of grandeur, began to work their magic. “Lengthily and profoundly I pondered where my duty lay,” she confided. “The clouds were heavy over Europe at that time and several British submarines had been attacked anonymously, so to speak, in Spanish waters. Had I the right to selfish consideration?”

When the inventor proposed again, she said yes. For the sake of humanity, she assures us. She built him a special research laboratory at her chateau in France. But as the war encroached she was forced to leave, and while re-establishing herself back in Manhattan, where she’d lived off and on since 1916, she learned that he’d died. Rather than fall apart, she finished up her memoir, proving herself to be, in life, as in her art, immune to setbacks.

As I read about Walska, I couldn’t decide: Did I like or loathe this woman? I very much did not like her chronic dependency on men, and money, and her obvious, outsize delusions. And yet I loved how, as only a true eccentric can, she refused to accept the label. She considered herself an “original in the true meaning of the word,” and “a pioneer in the field of feminine embellishment.” Closest to her heart were enormous jewels, “the biggest stones I could find on the market, the largest generous Nature created,” which she would buy in “any existing size and color”—including the Romanov sapphire and one of only two known 95-carat antique-cut yellow briolette diamonds—and have set in huge necklaces, bracelets, and rings of her own design, “twenty years before the actual fashion for big gems,” she claims.

Lotusland is all of Walska’s drama and eccentricity writ large, in plants—an autobiographical garden, if you will.

Indeed, this personal passion led to her to transform American tax laws: On her third American concert tour, in 1928, after U.S. Customs tried to collect an import duty of $1,000,000 on her traveling wardrobe and jewels, assessed at $2,500,000, she fought the Third Division of the U.S. Customs Court, “as a feminist, to establish the principle that a woman’s residence is where she lives and not where her husband lives.” She won.

At last, in 1941 she sent the 501-page Always Room at the Top off to her publisher, dedicated to her fellow travelers, “All those who are seeking their place in the sun.” Did she have any idea that, between the manuscript’s completion and its publication in 1943, she’d be badgered into yet another marriage, this time to a handsome Arizona-born Tibetan Buddhist who was 21 years her junior? Probably.

What I do know—thanks to the internet, that vast keeper of all the world’s secrets—is that the “White Llama,” as her yogi was known, would prove to be such an unrepentant con artist that they’d divorce in three years’ time, at which point she’d finally be free to actually find inner peace. That is, she didn’t find it until she’d finally stopped trying. Such are the dramatic perks of reading the autobiography of a long-dead person: We know how their lives turn out before they do.

Early in her memoir, Walska writes, “Around forty I understood with a touching sadness that my dreams, those constant reveries conceived in the abstract, had not materialized. I realized that youth was already behind me.” But she was wrong about that. All her life, she’d relied on men to fund her constant reveries. It wasn’t until late middle age, after she’d published the memoir, after she’d risen from the ashes of that sixth and final marriage, that she freed herself from abstractions and finally figured out how to express herself. Singing wasn’t her vocation after all. It was plants.

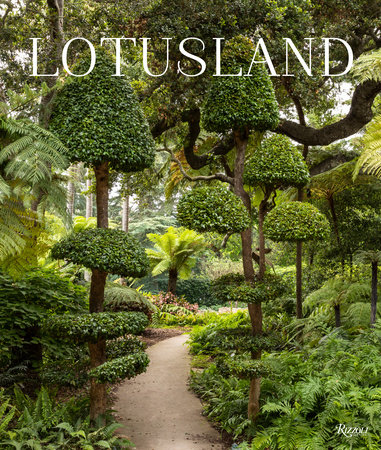

In 1941, while still with the White Llama, she’d bought a 37-acre estate in Montecito, California, intending to create a retreat for Tibetan monks (and safeguard her finances; she’d seen Polish and Russian aristocrats reduced to poverty during WWI, and wasn’t about to meet the same fate as America headed toward another). After the divorce, alone at last, she moved out of the mansion and into the three-room pavilion attached. For the next 43 years, she threw herself headlong into creating one of the most unusual botanical gardens in the world, which she called Lotusland.

Lotusland is all of Walska’s drama and eccentricity writ large, in plants—an autobiographical garden, if you will. Today, it is open to the public. There are 19 distinct gardens in all, each its own theatrical event, as if the plants are props and performers arranged on a stage. The Cactus Garden could be a forest on Mars. The Butterfly Garden is an “insectary” of various flowering plants that attract insects. My favorite part of Lotusland isn’t a garden at all, but the 20 or so three-foot-long clamshells planted like a fleet of elegant satellite dishes beside an aqua-blue swimming pool.

Walska worked the gardens every day, always wearing her medals—an Order of Merit from Poland, and two Medals of Honor from France. Eventually, as her arthritis worsened, she gardened while walking with two canes. In 1982 she broke her hip, and died two years later, age 96. Herself to the last.