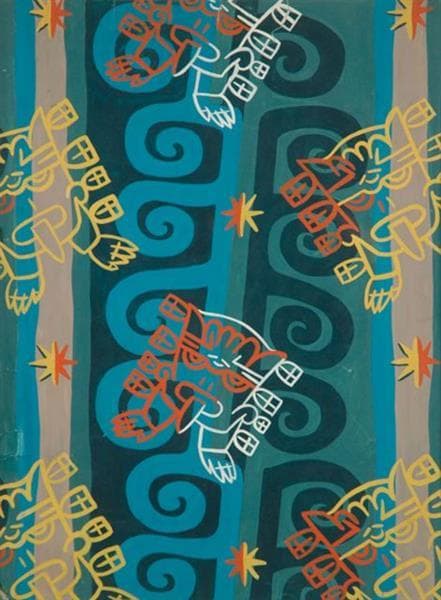

Her paintings have hung in the White House and are in the permanent collections of major museums like The Met, but some of Lois Mailou Jones’ most vibrant work was created for an entirely different kind of canvas: textiles. Before she was known as a painter, this art-world pioneer worked as a successful pattern designer for high-end firms like the F.A. Foster Company and yes, even Schumacher.

Why pioneering? In 1927, she became the first Black graduate of Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Her talent, recognized early, led to multiple art school scholarships, where she quickly mastered pattern design and was immediately successful in the field: her patterns were reproduced and sold all over the U.S. by the time she was just 22 years old. Looking at the work, it’s easy to see why. Her designs still feel fresh, relevant and even modern nearly a century later. The colors are vibrant and alive, and the designs burst with a terrific optimistic energy. They also incorporate a host of motifs ranging from Caribbean flora to Navajo weaving and African statuary, showing her early curiosity and deep well of artistic influences.

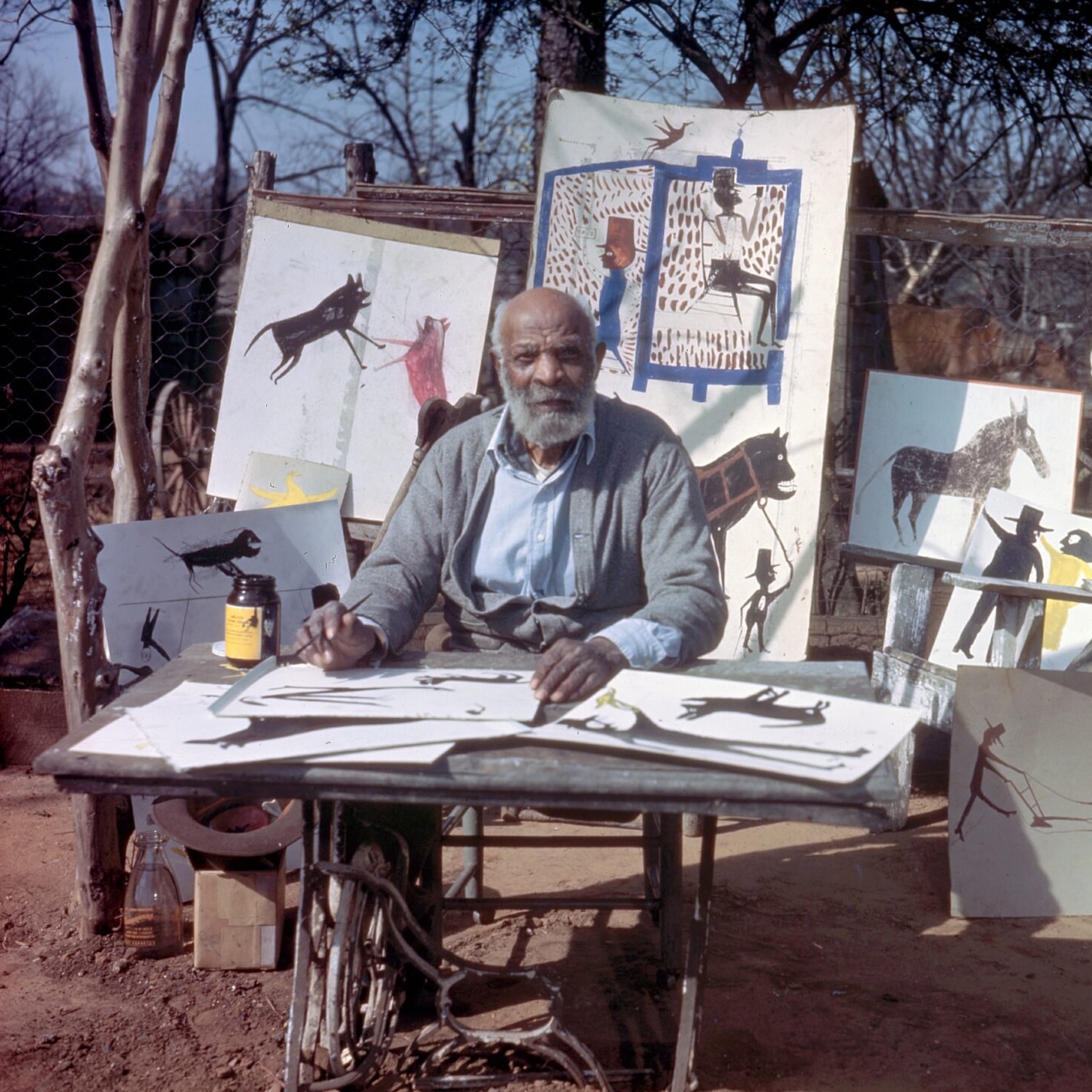

Despite the success and the pride of seeing her work in interior design shop windows, Jones wasn’t satisfied. “I realized that my name was…never published with the designs,” she told an interviewer in 1989. “As I wanted my name to go down in history, I realized that I would have to be a painter. And so it was that I turned immediately to painting.” She applied for teaching jobs in Boston to support herself, but was told she should “go South and help her people.” After a short stint at a prep school for Black students in North Carolina, Howard University recruited her to join their art faculty, where she stayed for nearly 50 years. During that time, she spent a liberating year in 1930s Paris, where she became friends with Josephine Baker. Soon after her return, her richly hued impressionist landscapes began winning competitions at prestigious institutions like the Corcoran Gallery of Art at a time when Black artists were banned from participating (she had to ask white friends to submit her entries).

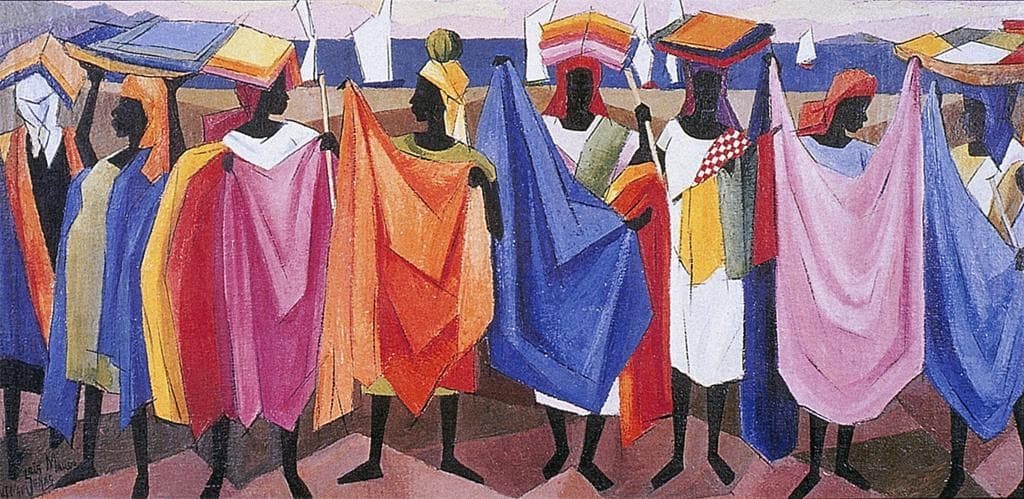

Travel invigorated her work again in the 1950s; in the following decades, she spent extended periods in Haiti and Africa, places that increasingly influenced her work in later life. Her paintings became more geometric, boldly graphic, but the intense colors remained a hallmark. Long overdue recognition finally found her in 1980 when President Jimmy Carter presented her—at the age of 75—with an award for Outstanding Achievements in the Arts at a White House ceremony. She continued working and winning accolades up until her death in 1998. As for the Corcoran Gallery, which denied blacks the right to enter its painting competitions, the museum threw Jones a party on her 89th birthday, and officially apologized for its racist behavior.